By Olayinka David-West (Professor of Information Systems, Lagos Business School) and Immanuel Umukoro

Nigeria launched the eNaira, Africa’s first central bank digital currency (CBDC), on October 25, 2021, as part of the country’s larger shift toward digital payments and away from cash. The eNaira provides Nigeria’s younger population access to secure cryptocurrency payments and alignment with existing policy initiatives like the Cash-Less Nigeria policy and the National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS).

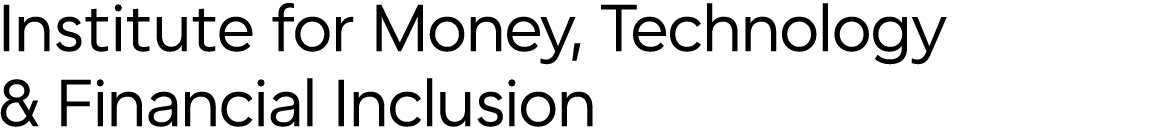

Yet, even though Nigeria has seen significant technological advancements in banking and payments, the Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) drive for a cashless economy has yet to reduce cash usage in Nigeria’s informal economy, even with the existence of digital payments systems like the NIBSS Instant Payments (NIP) solution. While digital payment transactions surge (Figure 1), the amount of currency in circulation is also on the rise.

Although CBN’s cashless policy does not aim to eliminate the use of cash, low trust in formal financial institutions and mixed perceptions about the reliability, availability, security, accessibility, and interoperability of digital payments systems limits their adoption.

Figure 1. Electronic payments transaction volumes by type. (CBN Statistics database)

Nigeria’s eNaira is an account-based retail CBDC with the slogan “Same Naira, More

Possibilities.” It employs a two-tiered architecture with regulated financial institutions

and registered agents acting as intermediaries. With about half of Nigeria’s adult

population lacking access to formal financial services, the CBN expanded the existing

three-tiered Know Your Customer (KYC) regulatory framework, including a tier 0 for

non-account holders that have a mobile telephone.

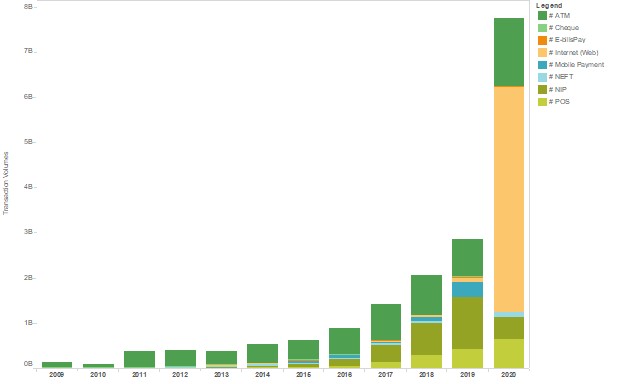

The CBN hopes that the eNaira will create seamless payment opportunities; reduce cash leakages, settlement risk, and cash dependency; drive financial inclusion; and increase seigniorage by reducing the cost of physical money management. In addition, the eNaira is expected to protect the public against the volatility of private virtual currencies, such as cryptocurrencies. Despite these advantages, the pilot launch targeting banked Nigerians with smartphones produced only 6,340 active wallets after six months (Figure 2).

Figure 2. eNaira adoption as of April 2022. (CBN)

This blog post presents early research (Figure 3) findings from a Lagos Business School (LBS) study, supported by Maiden Labs, highlighting the mixed reactions about the eNaira and potential pathways to driving widespread adoption.

Figure 3. Focus group discussion with transport workers. (Photo credit: Immanuel Umukoro)

Strong Value Proposition

While some believe the eNaira has the potential to be a game changer in Nigeria’s

financial inclusion journey, others believe it offers no value offerings beyond what

existing payment systems offer. This perceived competition with existing payment solutions

was the reason given by 49% of the study participants who did not intend to use the

eNaira. The small group of users (5.8% of the survey population) who were early adopters

signed on to the product primarily because it was a new trend and people were talking

about it. Another 37% said they would use eNaira if it addressed their pain points,

such as high transaction charges, failed transactions, and low merchant acceptance.

Despite the perceived benefits of the eNaira, the system needs strategies to build

awareness and drive adoption to increase its use and efficacy in addressing financial

inclusion.

Insufficient Use Cases

The eNaira is a digital platform that is plagued by the proverbial chicken-and-egg

problem and lacks positive network effects. Transaction numbers remain low: 10% of

eNaira users have only carried out between five and ten transactions, highlighting

low merchant adoption (Figure 2) and the eNaira’s limitations as a payment system.

Currently, most people use the system for person-to-person (P2P) transfers among users

and setting money aside (savings). Some ways to increase adoption and use include:

(1) having places to use the payment mechanism by increasing merchant acceptance (Figure

4), especially among Nigeria’s vast informal sector; (2) supporting inbound international

remittances; (3) earning interest on wallet deposits; and (4) offline access via agents

and other channels.

Figure 4. Poultry seller. (Photo credit: SIDFS)

Disintermediation of Banks

The eNaira’s two-tiered architecture mandates deposit money banks (DMBs) play a critical

role in its distribution. However, their plausible disintermediation and potential

revenue loss threaten their business models and support for the eNaira. As explained

by a bank executive:

“There must be something for us inside. We are not staff of CBN, and we don’t work with CBN. If there’s anything that will interfere with my NIP fee, which speaks directly to my income, my appraiser, my bottom line, e-Naira must solve that problem. Otherwise, I see it as cannibalizing my portfolio. So, there must be something for us as a bank.”

Conclusion

The evidence supports revisiting the eNaira’s design, adoption strategy, and operating

model. The design should further consider and clarify its impacts on money and monetary

policy, as well as cross-border remittances. Stakeholders must collectively address

the additional levels of competitiveness of the broader financial system and issues

around consumer protection. Finally, technological considerations relating to trust

and privacy, either by design or by policy, will affect its use.

While the eNaira pilot targeted banked Nigerians, extending the product across excluded segments will require different strategies and alignment with national policies like the National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS). Such strategies should focus on ensuring the eNaira better complements existing payment systems for the banked, while also securing it as a better substitute for cash alongside existing KYC amendments for the unbanked.

The operating model is the last component requiring attention. This includes the entity managing the eNaira and business management factors like marketing, communications, and distributing, delivering, and managing the eNaira to all Nigerians, alongside disadvantaged and vulnerable groups like the elderly. The CBN should pay careful attention to product design and technology development, especially user interface (UI) and user experience (UX).

The eNaira system is constantly changing. Since completing this research, the CBN

has improved the app and introduced capabilities to onboard unbanked customers using

a national identity number (NIN) and support users who don’t have smartphones by offering

an unstructured supplementary service data (USSD) interface. One year after introducing

the eNaira, the CBN continues to educate industry stakeholders about the digital currency

and its benefits. At the one-year anniversary forum, discussions addressed topics

like extending eNaira use cases through collaborations (public-private, private sector,

and government-government) that facilitate resilient financial infrastructures and

interoperability, improving Nigeria’s digital infrastructure by implementing the National

Broadband Plan and building consumer awareness through literacy programs. Indeed,

Nigeria has embarked on this journey that promises more possibilities with the same

Naira.

About the Nigerian eNaira Research

This project was carried out using a mixed-method approach involving respondents drawn

from the regulatory, financial services, and consumer segments. On the supply side,

using semi-structured interviews, we engaged experts drawn from banks, licensed mobile

payment providers, payment infrastructure providers, and financial services regulators.

On the demand side, we conducted five focus group discussions with 54 current and

potential users and followed this with a broader survey of 348 respondents across

Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones. Prof. Olayinka David-West led this project with

the help of Immanuel Umukoro and the support of Maiden Labs and the Institute for

Money, Technology & Financial Inclusion (IMTFI).

This work was conducted as an independent 2022 research project on central bank digital currency and financial inclusion, in collaboration with Maiden Labs, the MIT Digital Currency Initiative, and the Institute for Money, Technology & Financial Inclusion, and funded by the Gates Foundation. You may view the context of this study on the IMTFI blog and details of the new research report release here.

Original blogpost published on the IMTFI Blog on February 23, 2023 can be found here: CBDC Field Research Insights: Nigeria’s eNaira – Enabling Possibilities