Project Year

2009

Region(s)

South Asia

Country(ies)

India

Project Description

This study focuses on the financial behavior of rickshaw pullers, many of whom come from rural areas to work in the city, and are chronically poor. The study will survey 125-150 rickshaw pullers in Delhi through intensive and detailed questionnaires (to be developed). In addition, 25 key informants drawn from those relating to the rickshaw pulling sector (rickshaw owners/contractors, mechanics, and users of rickshaws) will be interviewed.

Researcher(s)

Mani A. Nandhi

About the Researcher(s)

Synopsis of Research Results

Case studies of Parichan and Mohan:

Parichan and Mohan are two Delhi rickshaw pullers who live their lives on the streets.

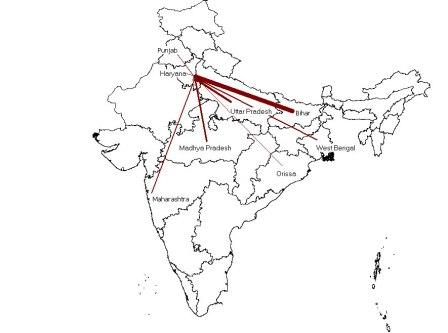

Like over half of the research sample of 177 rickshaw pullers, they migrated to Delhi

from Bihar. Parichan left his home 25 years ago never to return to his village in

SitamarhiDistrict. He is alone and has no contact whatsoever with his extended family

and has made the Delhi streets his home since he migrated there. With no one to help

him in Delhi, he saw rickshaw pulling as a means of livelihood. He has made the footpaths

of Ajmeri Gate his home and uses either a paid public lavatory or bath, or the free

public taps and public spaces as his washroom.

Parichan and Mohan are two Delhi rickshaw pullers who live their lives on the streets.

Like over half of the research sample of 177 rickshaw pullers, they migrated to Delhi

from Bihar. Parichan left his home 25 years ago never to return to his village in

SitamarhiDistrict. He is alone and has no contact whatsoever with his extended family

and has made the Delhi streets his home since he migrated there. With no one to help

him in Delhi, he saw rickshaw pulling as a means of livelihood. He has made the footpaths

of Ajmeri Gate his home and uses either a paid public lavatory or bath, or the free

public taps and public spaces as his washroom.  |

His reasons for saving with these different sources are simple. He deposits with them

because he has known them since he came to Delhi, but also finds them trustworthy,

convenient and accessible to deposit his day’s earnings. To a question on whether

he had any account in a bank or a post office, he stated that he never thought of

these possibilities. He added that he tried to open a bank account 20 years back but

was told to get an ID. He asks, “where do I go for it when I have no identity living

on Delhi streets?” Parichan has never borrowed money for any purpose but takes or

gives shorthand loans with his fellow pullers. When he borrows, he ensures he pays

back in two days.

His reasons for saving with these different sources are simple. He deposits with them

because he has known them since he came to Delhi, but also finds them trustworthy,

convenient and accessible to deposit his day’s earnings. To a question on whether

he had any account in a bank or a post office, he stated that he never thought of

these possibilities. He added that he tried to open a bank account 20 years back but

was told to get an ID. He asks, “where do I go for it when I have no identity living

on Delhi streets?” Parichan has never borrowed money for any purpose but takes or

gives shorthand loans with his fellow pullers. When he borrows, he ensures he pays

back in two days.

In contrast to carefree Parichan, 19 year old Mohan dropped out of school when he

was 12 because his father, then in failing health, could not work any more as a dhobi

(washerman). As the eldest son, he became responsible for his parents and two younger

siblings. So he migrated 5 years ago from Samastipur district in Bihar to Delhi, to

find employment. His cousin’s brother was working there, and he moved in with members

of his brother’s family. He started out as a wage labourer in constructing mobile

towers for a telecom company. However, after 6 months at that job, he switched to

rickshaw pulling. Unlike the wage job, which paid him the same amount no matter how

hard he worked, as a rickshaw puller he found he could earn a little more by pulling

more rides. He owns a mobile phone to keep in touch with his family, and a watch.

In contrast to carefree Parichan, 19 year old Mohan dropped out of school when he

was 12 because his father, then in failing health, could not work any more as a dhobi

(washerman). As the eldest son, he became responsible for his parents and two younger

siblings. So he migrated 5 years ago from Samastipur district in Bihar to Delhi, to

find employment. His cousin’s brother was working there, and he moved in with members

of his brother’s family. He started out as a wage labourer in constructing mobile

towers for a telecom company. However, after 6 months at that job, he switched to

rickshaw pulling. Unlike the wage job, which paid him the same amount no matter how

hard he worked, as a rickshaw puller he found he could earn a little more by pulling

more rides. He owns a mobile phone to keep in touch with his family, and a watch.

Mohan learned the hard way about saving his money. When he was a newly-arrived migrant in Delhi, he started depositing his daily earnings with a local shopkeeper in Subhash Nagar, like most rickshaw pullers do. After 25 days, he requested the shopkeeper to give his money back. But the shopkeeper told him he would not return it to him for two more weeks. He waited 15 more days. When he asked for his money, the shopkeeper denied ever taking his savings, and turned the tables on him, saying “you are a liar, you never handed any money to me!” So Mohun lost his money, and his faith in saving with any other person.

After this incident, he kept his saved earnings himself – in a small locked luggage bag in his shared quarters, or on his person in a plastic bag. He absolutely had no idea about other saving options – either formal (bank or post office) or semi-formal. He was very eager to have a safe saving option. As he stated, ‘It is always problematic to keep saved money with oneself; there has to be some way for keeping money safely for poor like me’

He had been ill for about two weeks prior to the field interview; as a result he could not pull regularly, and his net earnings for two days was Rs.200 [US$4]. During this illness, he partially used his savings and partially borrowed from a rickshaw puller friend. Though he does not buy food on credit, he owed Rs210 to his rickshaw owner for hiring the rickshaw on credit. He had to borrow twice from a moneylender in his village last year – one loan of Rs.5000 for his father’s medical expenses and a second loan of Rs.4000 for fulfilling family/social obligations when his paternal uncle’s son got married. Both the loans were taken at a 7 percent monthly interest rate. He had cleared off most of the loans except for Rs.2000, which is still outstanding.

For someone so young, he worries constantly about managing food expenses, debt repayments, and festival and educational expenses for his family. He became emotional in talking about providing an education for his younger siblings, because he loved to study but had to discontinue his schooling because of his poverty. He reads newspapers when he gets time, but does not like to waste time because it means a foregone opportunity to pull another ride and earn a little more money.

Read Nandhi's Final Report, "The Urban Poor and Their Money: A Study of Cycle Rickshaw Pullers in Delhi" (June 2011).

Read Nandhi's presentation Savings Behaviour of the Urban Poor, given at the Microfinance Researchers Alliance (MRAP) Program at the Centre for

Microfinance in Chennai on 6th August 2010.